In the age of interconnectedness and big data, the protection of personal information has emerged as a critical concern. Of all forms of personal data, perhaps none is as sensitive as healthcare information. An individual’s healthcare data could include everything from basic identification details to genetic markers, from prescription records to mental health notes—information that could be used unethically if placed in the wrong hands. This is where the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) comes into play. Enacted into federal law by the United States Congress in 1996, HIPAA has undergone several updates and modifications but remains a cornerstone in the regulation of healthcare information. Its primary aims are to safeguard the privacy and security of healthcare data, while also facilitating the portability of health insurance coverage across employers. Though HIPAA has been around for decades, misunderstandings about its provisions, coverage, and enforcement are still widespread. This article aims to serve as an exhaustive guide on HIPAA, shedding light on its key aspects, historical evolution, and how it impacts various stakeholders including healthcare providers, patients, and third-party vendors.

What is HIPAA?

Historical Context

The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, commonly referred to as HIPAA, is a seminal piece of federal legislation that has left an indelible impact on the healthcare industry in the United States. It was enacted on August 21, 1996, by the 104th United States Congress and was signed into law by President Bill Clinton. At the time of its enactment, the healthcare industry was undergoing rapid changes, with an increasing shift toward digitization and electronic records. The two-fold challenge was to facilitate this transformation while also ensuring the privacy and security of patient information. To address these concerns, HIPAA was crafted to serve multiple purposes, the foremost of which were to streamline healthcare transactions, guarantee the portability of health insurance across jobs, and mandate the protection of patients’ healthcare information.

Key Objectives

HIPAA was originally aimed at achieving two major objectives:

- Portability: The act sought to address the issue of ‘job-lock,’ whereby individuals were hesitant to switch jobs due to the risk of losing health insurance coverage. Under HIPAA’s provisions, individuals could transfer and continue their health insurance coverage when they changed or lost their jobs.

- Accountability: As healthcare institutions increasingly moved towards electronic data storage and transactions, the necessity for stringent data protection measures became evident. HIPAA introduced standards to govern the electronic transmission of health data and outlined regulations for the secure storage, transmission, and processing of what it termed ‘protected health information’ (PHI).

Scope and Provisions

Over the years, the scope of HIPAA has significantly widened to include not just healthcare providers like hospitals and clinics, but also other entities that handle PHI, such as insurance companies and pharmacy benefit managers. With technological advancements, the understanding of what constitutes PHI has also expanded. Today, PHI includes a wide array of information ranging from medical records, treatment histories, and test results to billing records and even IP addresses of individuals. To ensure the secure management of this sensitive data, HIPAA set forth a series of national standards.

- Privacy Standards: HIPAA’s Privacy Rule regulates how healthcare information should be controlled, stipulating under what circumstances PHI can be used or disclosed. This includes provisions for patient consent and rights over their own healthcare data.

- Security Standards: The Security Rule of HIPAA is targeted at safeguarding electronic PHI (ePHI). It mandates covered entities and their business associates to implement administrative, physical, and technical safeguards to ensure the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of ePHI.

- Transactional Standards: To facilitate electronic healthcare transactions, HIPAA standardized the codes and formats for common healthcare transactions such as billing, making it easier for different healthcare providers and payers to communicate electronically.

- Enforcement: HIPAA includes civil and criminal penalties for violations, and enforcement activities are carried out by the Office for Civil Rights (OCR) within the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS).

By setting these standards, HIPAA has played a pivotal role in shaping the landscape of healthcare information management in the United States, making it one of the most comprehensive healthcare data protection frameworks globally.

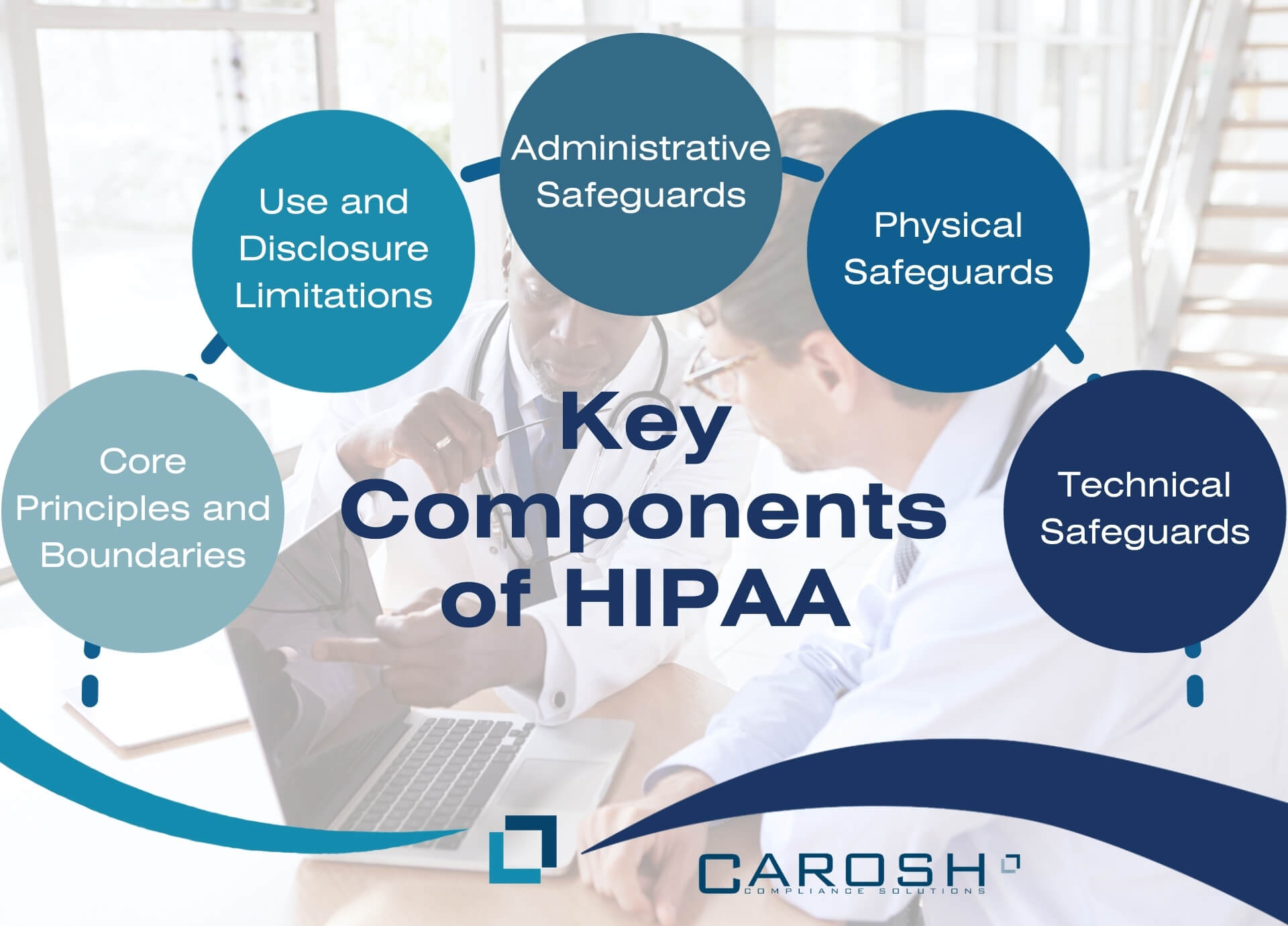

Key Components of HIPAA

Core Principles and Boundaries

The Privacy Rule serves as one of HIPAA’s central pillars, focusing primarily on the handling of Protected Health Information (PHI). The term “covered entities” is an inclusive one, embracing healthcare providers such as doctors, clinics, and hospitals, as well as health plans like insurance companies, and healthcare clearinghouses that process health information.

Use and Disclosure Limitations

The rule meticulously outlines the circumstances under which PHI can be used or disclosed without explicit patient consent. It’s not a carte blanche for healthcare providers or other covered entities. Rather, it specifies a set of conditions, such as the need for treatment, payment, or operational procedures like quality assessments and audits, where PHI disclosure is permissible.

Administrative Safeguards

These safeguards encompass a broad range of policy-driven administrative actions, procedures, and guidelines aimed at managing the selection, development, implementation, and maintenance of security measures to protect electronic PHI. This includes elements like a security management process, workforce security clearance, and ongoing security training and awareness programs.

Physical Safeguards

While digital security is often the primary focus, the physical protection of data repositories cannot be overlooked. Physical safeguards might encompass measures such as surveillance systems, controlled facility access and validation procedures, and maintenance records for physical access controls.

Technical Safeguards

These are essentially the technology-driven measures that are implemented to protect electronic PHI. These might include access controls, encrypted data transmission, and regular audits to ensure ongoing security. Importantly, the Security Rule is technology-neutral, allowing healthcare organizations the flexibility to implement technologies that are best suited to their operational needs while ensuring compliance.

HIPAA and Business Associates

Scope and Contracts

The tentacles of HIPAA extend beyond traditional healthcare entities, reaching into the realm of business associates. These could range from legal advisors to cloud storage providers who handle PHI. Business Associate Agreements (BAAs) are contractual stipulations that bind these third parties to HIPAA compliance, mandating them to implement appropriate safeguards to ensure the confidentiality and integrity of PHI.

Notable Provisions

“Minimum Necessary” Rule

One of the cornerstone provisions of HIPAA, the “Minimum Necessary” Rule mandates that only the least amount of data needed to accomplish a given task should be used or disclosed. This inherently builds a layer of security by limiting the scope of PHI that is exposed during any given transaction.

Patient Rights

HIPAA isn’t merely a set of prohibitions and guidelines for healthcare entities; it also empowers patients. Patients have the right to inspect, copy, and amend their own health records. They also have the right to receive an accounting of non-routine disclosures of their PHI, offering a level of transparency that bolsters trust in the healthcare system.

The obligation of covered entities to inform affected parties in case of a data breach offers a level of accountability and transparency. It’s a mechanism to ensure that data custodians act responsibly and are penalized for lapses in securing PHI.

Enforcement and Penalties

The Office for Civil Rights (OCR), a branch of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), shoulders the responsibility of enforcing HIPAA. Penalties for non-compliance are tiered, varying in severity based on the degree of negligence involved. These can range from moderate fines for unintentional violations to criminal charges leading to imprisonment for willful neglect without corrective action.

HIPAA in the Digital Age

In the modern landscape with electronic medical records, telemedicine, and IoT healthcare devices, HIPAA has found renewed relevance. Its guidelines and principles serve as the framework governing how new-age healthcare technology interacts with PHI, ensuring both innovation and data protection go hand in hand.

Implications for Healthcare Providers

For providers, complying with HIPAA is an intricate exercise involving multi-pronged strategies:

- Training: Continual staff training on HIPAA guidelines is crucial to mitigate risks.

- Risk Assessment: Regular internal and external audits are imperative to identify vulnerabilities.

- Policies and Procedures: Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) need to be in place to ensure every team member knows their role in maintaining HIPAA compliance.

Implications for Patients

For patients, HIPAA represents a safety net. It ensures their sensitive healthcare data is treated with the respect and confidentiality it deserves, giving them confidence to interact with healthcare systems.

Challenges and Criticisms

HIPAA is not without detractors. Critics argue that the law may impede medical research and create barriers to data sharing. The complexity and costs of compliance are also cited as burdensome, particularly for smaller healthcare providers.

Conclusion

HIPAA’s role in the healthcare ecosystem is monumental. It’s a balancing act between ensuring data privacy and security while allowing for operational flexibility and technological innovation. As healthcare paradigms shift with emerging technologies, HIPAA will inevitably evolve. But its fundamental objective—to maintain the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of PHI—will remain unchanged.

By deeply understanding HIPAA, we not only fulfill a regulatory mandate but also honor an ethical commitment to protect the healthcare data that forms the bedrock of patient trust and care quality.